From OLED to Tegra: Five Myths of the Zune HD

Just when you thought Microsoft had given up on the Zune as a product and had retreated to referring to it as a nebulous cloud of conceptual features, the company comes out with a new device supporting a mobile-optimized OLED screen, a wildly powerful yet super efficient new multi-core Tegra graphics processor and support for high definition radio. The problem is that none of those things are actually true.

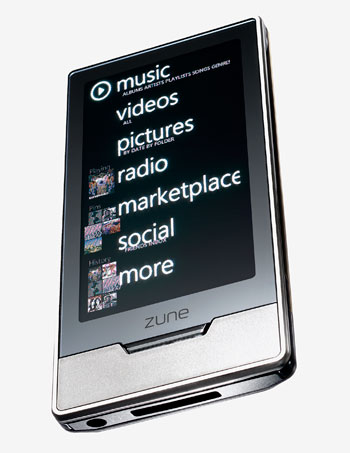

With the Zune HD, Microsoft has dusted off its failed brand and applied it to a new device aimed at the iPod touch. To distinguish it, the company has added several new features. Unfortunately, as was the case with previous models, what Microsoft has added is all sizzle and no steak. Here’s why.

Myth 1: OLED is a great display technology for mobile devices

First off, Microsoft gave the Zune HD a new OLED display. OLED is an interesting new technology that uses a layer of electroluminescent organic compounds, rather than the inorganic materials used in traditional LCDs, to produce an image. OLED panels don’t require a backlight, so they can render true blacks and provide a higher contrast ratio.

However, today’s OLED panels are much dimmer than standard issue LCDs: a typical maximum output of 200cd/m^2 compared to around 4-500 for mid-range LCDs. OLED also performs considerably worse in bright light because OLED is 100% emissive rather than being partially transflective.

A good quality LCD actually uses ambient light to make its image brighter and more vibrant; OLED does not. This means when you take it outside, the OLED’s screen is completely washed out by sunlight. Unless you only plan to use your mobile device in your dark basement, you don’t want one of today’s OLED screens, particularly on a mobile media player that you might expect to use on the go in various environments.

A shot in the dark

Microsoft knows this, which is why it only demonstrates the Zune HD in dark rooms. Engadget filmed a full demonstration, including the device’s incapacity to pull up a web page, in a suspiciously dark room without even noting this. There are actually candles visibly flickering in the video behind the device.

Microsoft sets up its demos in the dark because the Zune HD looks terrible outside, where its contrast ratio advantage observed in ideal conditions completely falls apart. Engadget’s other pictures of an OLED-using Sony Walkman show that without the candle-lit smoke and mirrors, OLED blacks are not black at all.

There are other problems with OLED. They don’t last long, because the electroluminescence layer degrades far more rapidly than regular LCDs. Component colors within OLED also die at different times, with the blue pixels fading first. This results in a rapid shift of the color balance as the device ages. Additionally, the original color reproduction gamut of brand new OLED displays is already worse than standard LCD, resulting in less natural-looking colors from the start that only get worse.

More power to ya

And despite the power savings attributed to OLED’s backlight-free design, OLEDs still use more power than LCD displays most of the time because the OLED technology consumes power based on how bright the image it is displaying is. Essentially, OLED is the backlight.

Sony and Microsoft try to compensate by giving their OLED devices a dark, mostly black user interface. Unless you will exclusively be using your Zune HD to watch gothic movies in the dark, the screen will be gobbling up more power than an LCD. This is particularly the case if you want to browse the web, which involves a lot of white space. Showing a white background, OLED consumes as much as 300% of the power of an LCD. Any colors that rely upon those those fragile blue pixels are particularly power inefficient.

And again, because OLED doesn’t use any ambient light to brighten its picture, as LCD does, 100% of the image comes from emitted light output, which requires a bigger drain on the battery. For this reason, reviewers of other OLED products have expressed puzzlement about why the supposedly efficient OLED technology didn’t translate into better battery life in actual use, as did the Register when looking at a Samsung s8000 Jet:

"Considering it’s got an energy-saving OLED screen, we were disappointed with the battery life of the Jet. Perhaps the powerful processor puts some extra drain on the juice, but the promised 180 minutes of talk time and 250 hours’ standby translated into a barely a day of moderate use."

If you’re wondering why Apple, which sells tens of millions of mobile devices per year and has a component appetite that literally sways RAM markets, didn’t beat Microsoft, a company that barely sold a couple million Zunes in two years, to the OLED trough, it’s not because Microsoft is on the cutting edge, but because Microsoft is desperately looking for a marketable feature, whether or not that feature makes any sense for consumers.

Myth 2: NVIDIA’s Tegra processor leapfrogs existing mobile processors

Now that you’re no longer in the dark on the oversold OLED, what about the Tegra processor used by the Zune HD: is it really the miracle chip that it is billed to be, both achieving spectacularly unprecedented performance and industry-leading power efficiency? Has Apple’s expertise in developing ARM CPUs and in running its own CPU fab plant been outmatched by Microsoft’s first foray into mobile devices with a functional web browser?

The Tegra is built by NVIDIA, leaving Zune fans to suggest that it delivers industry leading, desktop-gaming type graphics that far exceed the capabilities of industry-standard mobile graphics. However, Tegra isn’t a scaled down version of NVIDIA’s PC graphics GPUs. Instead, it’s based on technology NVIDIA acquired in its purchase of fabless chip designer PortalPlayer in 2007.

If PortalPlayer sounds familiar, it’s because Apple formerly used its system-on-a-chip parts to build MP3 players up through the 5G iPod and the original iPod nano. Apple accounted for 90% of PortalPlayer’s business when it dumped the company in 2006, reportedly because the company was arrogantly jerking Apple around. PortalPlayer was devastated and never recovered.

When NVIDIA acquired PortalPlayer for $357 million the next year, Wedbush Morgan Securities analyst Craig Berger observed, "This deal comes as a surprise to us as we believe there are other semiconductor firms that offer more technology for less money," and added that NVIDIA apparently "thinks it has a better chance of penetrating Apple iPod (video) products if it owns and integrates PortalPlayer’s technology."

Apple, PA Semi, and the PowerVR deal

However, NVIDIA didn’t ever get back into the iPod market. Instead, Apple began sourcing SoCs from Samsung, bought its own fabless chip developer by acquiring PA Semi for just $278 million, and secured a secret design license for Imagination Technologies’ PowerVR SGX graphics cores.

So, while NVIDIA’s Tegra grew from the humble origins of the chip powering the video 5G iPod, the iPhone 3GS and the latest iPod touch models feature a mobile-optimized GPU core descending from the Sega DreamCast. While Imagination’s PowerVR GPU never made it into the desktop GPU market to rival the technology from ATI and NVIDIA, it has become the gold standard in mobile GPUs.

But the GPU is only half the story. Tegra uses a conventional ARM11 family CPU core (ARMv6), the same generation CPU core used by the original iPhone, the Zune, Nokia N95, and the HTC Hero. The Tegra’s CPU/GPU package also uses DDR1 memory, introducing significant real world RAM bandwidth limits no matter how powerful the embedded GPU core is rated to be in theoretical terms.

In contrast, the modern Cortex-A8 used in the iPhone 3GS, Palm Pre, Nokia N900, and Pandora game console represents the latest generation of ARM CPU cores. It also employs a DDR2 memory interface, erasing a serious performance bottleneck hobbling the Zune HD’s Tegra. It’s difficult to make fair and direct comparisons between different generations of technology, but NVIDIA’s own demonstrations of Tegra’s ARM11/integrated graphics show it achieving 35 fps in Quake III. The same software running on Pandora’s Coretex-A8 with SGX GPU core achieves 40-60 fps.

Tegra’s Core Problem

Tegra is also being hyped as providing "8 processing cores," but this is nonsense as it simply counts logical blocks common to all embedded SoC parts as "cores." The CPU in the Tegra is a single ARM11 core. Even if the Tegra did supply multiple CPU cores, the Windows CE kernel used by the Zune HD doesn’t support multi-core SMP so it couldn’t make any use of them.

Other mobile devices use multiple ARM processors for efficiency or cost savings, such as the original iPods which idled along using two low power ARM processors, or the Nintendo DS, which uses an ARM9 and ARM7 to handle different functions independently. However, there is nothing in the supposed "multiple cores" of the Tegra that offers anything comparable.

NVIDIA promotes Tegra as being "Ultra Low Power," but its standard ARM11 CPU doesn’t deliver anything that isn’t available in other ARM designs, nor any special power savings over more powerful and modern processors like the Coretex-A8 in the iPhone 3GS and latest iPod touch.

Again, if you’re wondering why Microsoft was able to score the NVIDIA Tegra "before" Apple, it wasn’t due to any mobile industry clout or hardware experience on Microsoft’s end, but rather simply due to the fact that Apple has its own resources for designing and building advanced, state of the art mobile processors, and didn’t need to buy into the desperate hype NVIDIA is using to promote the runner up technology of Apple’s former SoC vendor.